- Legends of the Flying Dutchman.

- TRAVELS, IN VARIOUS PARTS OF: EUROPE, ASIA, AFRICA, DURING A SERIES OF THIRTY YEARS AND UPWARDS. 1790

- A Voyage to New South Wales (London, 1795), by George Barrington. pp. 45-47.

- SCENES OF INFANCY: DESCRIPTIVE OF TEVITDALE. 1803

- The Flying Dutchman; Written on Passing Dead-Man's Island In the Gulf of St Lawrence, Late in the Evening, Sept. 1804.

- ヴァンダーデッケン望郷の便り、あるいは愛着ゆえの執着(1821)Vanderdecken's Message Home;*11 Or, The Tenacity Of Natural Affection

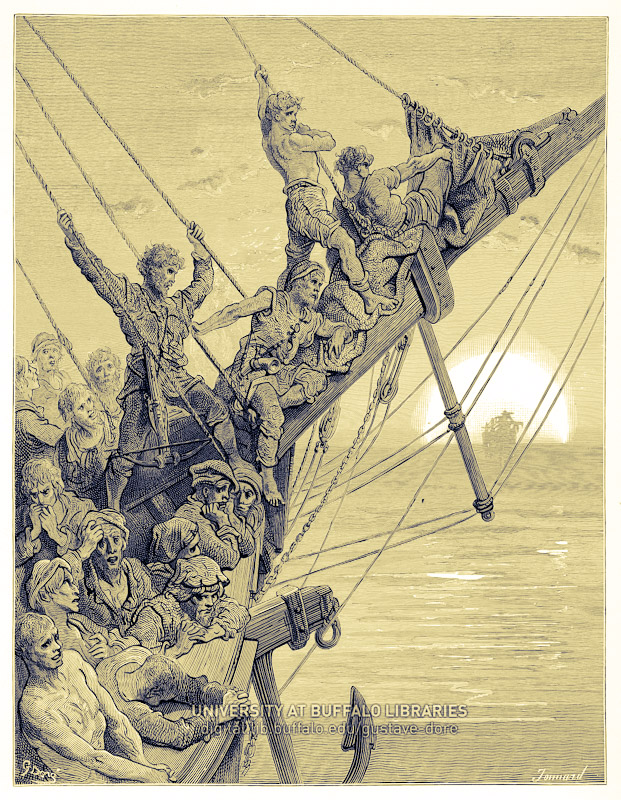

Legends of the Flying Dutchman.

コールリッジ『年寄り船乗り』を訳していて気になったのは、サルガッソにも「さまよえるオランダ人」にも言及がないことで、調べてみると伝説が形を整えたのは、1821年の小説 Vanderdecken's Message Home; Or, The Tenacity Of Natural Affection(作者不明)からであった。そもそもワーグナーの楽劇『さまよえるオランダ人』Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), WWV 63 は、直接にはドイツの詩人ハインリヒ・ハイネ『フォン・シュナーベレヴォプスキー氏の回想記』(Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski、1834)を元にしたワーグナー自身の台本によるのだが、そのまた元になるオランダ人伝説は、意外にも当時の出来立てに近い話であったのだ。

これについては、ピッツバーグ大学の D. L. Ashliman 教授が The Flying Dutchman

legends of Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 777*1 に纏めているから、アシュリマン教授が引用遊ばされた原典を参照しつつ翻訳してみた。

なお The Flying Dutchman の呼称は「さまよえるオランダ人」号と訳されてきたけれども、これは「さまよえるユダヤ人」に準えた表現であり、元はその快速を誇る「飛ぶように走るオランダ人」の意であったと思われるので、訳語を改変するか悩み中。

TRAVELS, IN VARIOUS PARTS OF: EUROPE, ASIA, AFRICA, DURING A SERIES OF THIRTY YEARS AND UPWARDS. 1790

BY JOHN MCDONALD. p.276

天候は非常に荒れ模様で、船乗りたちはさまよえるオランダ人が出たぞと称する程であった。よく聞く話では、このオランダ人は悪天候から喜望峰に逃れ来て、港に入ろうとしたところが、導くべき水先案内人が居らず、行方不明になってしまった。以来、大時化に遭うと、かの船の幻が現れるという。その船に向かって呼びかけでもしたら、普通に返事が来るぞと、船乗りたちは恐れ慄く。やがて私たちは貿易風に乗り、好天に恵まれたため、2週間はほとんど帆を動かさなかった。私たちは喜んでセントヘレナに下り、10日間停泊した。 陸上では、私はスチュワードの代理とテイラー船長の使用人を兼務。セントヘレナでは食事が早いので、私たちは毎日夕食後、白人農民に混じって田舎を歩いた。標高が高いので、海を見渡すことができ、農家の娘や白人の少女をたくさん見かけた。

The weather was so stormy, that the sailors said they saw the flying Dutchman. The common story is, that this Dutchman came to the Cape*2 in distress of weather, and wanted to get into harbour, but could not get a pilot to conduct her, and was lost ; and that ever since, in very bad weather, her vision appears. The sailors fancy that is you would hail her, she would answer like another vessel. At length we got into the trade winds, and had fine weather, so that we hardly shifted a sail for two weeks, when the ship's company had ease after hard work. We came down with pleasure to st. Helena,*3 and stopped ten days. On shore I was acting- steward, and Captain Taylor's, servant. As they dine early at st.Helena, we walked every day after dinner up the country amongst the white farmers. As the country is very high, we could see a great way at sea ; and up the country we saw a great many white girls, farmers daughters.

A Voyage to New South Wales (London, 1795), by George Barrington. pp. 45-47.

Superstition of the sea men - Story of the Flying Dutchman

幽霊船を畏れ敬う船員の迷信について聞くことはよくあったけれど、どうにも信じられない話だった。とあるオランダの戦闘艦が喜望峰から消え、船上の人ことごとく死に絶えて後、数年ほど。その僚艦は強風を凌ぎ、まもなくその岬に到着した。修理してヨーロッパに戻ったところ、ほぼ同じ緯度で激しい暴風雨に襲われ。夜警に立った若干名は見た、または見えたと思い込んだ。帆は畳み、此方が音を上げるまで追いかけてくる船を。うち1人は特に確言したもの、この前の強風で沈んだ船だと、あれは確かにあの船に違いない、あるいはあの船の幽霊だと。ところが空が明るくなってみると、その何物かも、厚く垂れ篭めた黒雲も、すっかり消えてしまったという。これを怪奇現象とする思い込みは、何を以てしても、船員の心から拭い去ることはできなかった。そんなこんなで港に到着したときの有り様も手伝ってか、この話は野火のように広がり、かの幻影と思われる姿は、さまよえるオランダ人と呼ばれるようになった。オランダ人からイギリス人に至るまで、これを知らない船員は居ない。滅多に見ないインド人も、乗船している者によっては、幽霊を見たふりをする程である。

I had often heard of the superstition of sailors respecting apparitions, but had never given much credit to the report; it seems that some years since a Dutch man-of-war*4 was lost off the Cape of Good Hope, and every soul on board perished; her consort weathered the gale, and arrived soon after at the Cape. Having refitted, and returning to Europe, they were assailed by a violent tempest nearly in the same latitude. In the night watch some of the people saw, or imagined they saw, a vessel standing for them under a press of sail, as though she would run them down; one in particular affirmed it was the ship that had foundered in the former gale, and that it must certainly be her, or the apparition of her; but on its clearing up, the object (a dark thick cloud) disappeared.

Nothing could do away the idea of this phenomenon on the minds of the sailors; and, on their relating the circumstances when they arrived in port, the story spread like wildfire, and the supposed phantom was called the Flying Dutchman. From the Dutch the English seamen got the infatuation, and there are very few Indiamen, but what has someone on board, who pretends to have seen the apparition.

夜中の2時ごろ、肩を激しく揺さぶられて目が覚めた。ハンモックから起き上がると、甲板長が明らかに恐怖と狼狽の表情を浮かべて私のそばに立っていた。

About two in the morning I was waked by a violent shake by the shoulder, when, starting up in my hammock, I saw the boatswain, with evident signs of terror and dismay in his countenance, standing by me.

「頼むぜ、相棒」と彼は言った、「棚の鍵を渡してくれ。神かけて、俺は目茶苦茶傷ついたから。というのも、ちょうど船首の風当たりを眺めていたら、『さまよえるオランダ人』号が全部盛りで、俺たちの真下までやってくるのを見つける羽目になったんだ。…見ればわかる、あの船だ。…下甲板の砲門をすべて開き、舳先と艫の灯火が、行動開始と言わんばかりに点灯しているのが見えた。この悪天候の中、どんな船でも下甲板の砲門を開き、音も立てずに凌ぐことなどできないだろうに。波は山のように高い。この緯度で遭難したオランダ人の亡霊に違いない。その亡霊は、強風が吹くといつもこの方角に現れると聞いたことがある。

"For God's sake, messmate," said he, "hand us the key of the case, for by the Lord I'm damnably scarified; for, d'ye see, I was just looking over the weather bow*5, what should I see but the Flying Dutchman coming right down upon us, with everything set -- I know 'twas she -- I cou'd see all her lower-deck ports*6 up, and the lights fore and aft, as if cleared for action.*7 Now as how, d'ye see, I am sure no mortal ship could bear her lower-deck ports up and not*8 sounder*9 in this here weather. Why, the sea runs mountains high. It must certainly be the ghost of that there Dutchman, that foundered in this latitude, and which, I have heard say, always appears in this here quarter, in hard gales of wind."

オランダ産[の酒]を一口、二口飲ませてから、「幽霊が怖いのか」と誂うと、彼は少し落ち着きを取り戻した。

After taking a good pull or two at the Holland's [a bottle], he grew a little composed, when I jokingly asked him if he was afraid of ghosts?

「そのことに関しては、わかるだろう」と彼は言った。「どうしたら、他の人間と同じようになれるものやら。俺はずうっと、そういうものがひどく苦手だった。子供の頃から、暗闇の中で教会堂を横切るには、口笛や大声を出さずには居れなかった。物の怪どもに仲間が居ると思わせるためだ、一人のときにしか現れないと聞いたことがあるからな。ところがだ、舵を執っていたジョー・ジャクソンに、船首を見ろと声をかけたが、奴には何も見えちゃいなかった。でも、俺にはどうかというと、この瓶と同じくらいはっきり見えたんだが」と言いながら、ジュネーブの瓶からもう一口飲んだ。

"Why, as to that, d'ye see," said he, "I think as how I'm as good as another man; but I'd always a terrible antipathy to those things. Even when I was a boy, I never could find it in my heart to cross a churchyard in the dark without whistling and hallooing, to make them believe I had company with me, for I've heard say they appear but to one at a time; for now, when I called to Joe Jackson, who was at the helm, to look over the weather bow, he saw nothing; tho', ask how, I saw it as plain as this here bottle," taking another swig at the Geneva.

そのような姿をしたものを見つけられるかどうか確かめたいという好奇心から、私も甲板に出て彼に付き添った。しかし、月がとても明るく輝き、雲ひとつない晴天だった。甲板にいた他の人たちから聞いたところでは、30分ほど前はとても曇っていたそうで、もちろん私は、どんな幻影が相棒をこれほどまでに不安にさせたのか、簡単に察しがついた。波は非常に高く、強風はむしろ強まり、我々は碇泊を続けた。朝になると、他の輸送船と別れていた。帆柱上からも1隻も見つからなかった。

Having some curiosity to see if I could make out anything that could take such an appearance, I turned out, and accompanied him upon deck; but it had cleared up, the moon shining very bright, and not a cloud to be seen; though, by what I could learn from the rest of the people who were on deck, it had been very cloudy about half an hour before, of course I easily divined what kind of phantom had so alarmed my messmate. The sea running very high, and the gale rather increasing, we continued to lay too, and in the morning found we had parted company with the rest of the transports, not one being discernable from the mast head.

SCENES OF INFANCY: DESCRIPTIVE OF TEVITDALE. 1803

SCENES OF INFANCY: DESCRIPTIVE OF TEVITDALE. 1803

by JOHN LEYDEN.

南緯の高緯度アフリカ沿岸には、船乗りたち共通の迷信がある。ハリケーンにしばしば「さまよえるオランダ人」と呼ばれる幽霊船が現れるというのだ。夜が明けると、光り輝く船の形が、トップセイルを翻しながら急速に滑走し、「風の目」の中をまっすぐに航行する。 この船の乗組員は、航海が始まったばかりの頃に何か恐ろしい罪を犯し、悪疫に冒されたと考えられている。 そのため、彼らはあらゆる港への入港を拒否され、然るべき償いが終わるまで、その死を遂げた海を漂い続ける運命なのだと。チョーサーは同じような罰について言及している。

ならず者が、心から十字を切るよう、

好色な庶民は、死んだ後にまで

苦しみに喘ぎつつ常に世をさまよう、

世界が恐怖のうちに過ぎるまで。

チョーサー『禽獣の集会』

It is a common superstition of mariners, that, in the high southern latitudes on the coast of Africa, hurricanes are frequently ushered in by the appearance of a specter-ship, denominated the Flying Dutchman. At dead of night, the luminous form of a ship slides rapidly, with topsails flying, and sailing straight in "the wind's eye."*10 The crew of this vessel are supposed to have been guilty of some dreadful crime in the infancy of navigation, and to have been stricken with the pestilence. They were hence refused admittance into every port, and are ordained still to traverse the ocean on which they perished, till the period of their penance expire. Chaucer alludes to a punishment of a similar kind.

'And breakers of the laws, sooth to sain,

And lecherous folk, after that they been dead,

Shall whirl about the world alway in pain,

Till many a world be passed out of dread.'

CHAUCER'S Assembly of Fowls .

The Flying Dutchman; Written on Passing Dead-Man's Island In the Gulf of St Lawrence, Late in the Evening, Sept. 1804.

by Thomas Moore

見たまえ、あそこの黒雲の下に何か、

飛ぶように滑り行く、不気味な小帆船か?

満帆に、いや風は凪いでいるのに、

あの船の帆は一杯に、吹かない風に!

SEE you, beneath yon cloud so dark,

Fast gliding along a gloomy bark?

Her sails are full,—though the wind is still,

And there blows not a breath her sails to fill!

何をする、闇を引きずるあの船は?

そこに在るは、墓場を占める静謐では。

今再び救われるべく弔鐘鳴らせ、

夜露の降りた帆のはためき。

Say, what doth that vessel of darkness bear?

The silent calm of the grave is there,

Save now and again a death-knell rung,

And the flap of the sails with night-fog hung.

荒れ果てた岸に残骸の横たわるもの

冷たく無情なラブラドールの

月の下、霜の降りた乗り物に。

数え切れぬ船乗りの骨を投げ積みに。

There lieth a wreck on the dismal shore

Of cold and pitiless Labrador;

Where, under the moon, upon mounts of frost,

Full many a mariner’s bones are tost.

あそこの影なる小帆船こそ、その難破船だったのでは、

青い鬼火が、あちらの甲板ぼんやり点くのは、

演出なのでは、蒼くも青い乗組員の。

教会の墓地の露を飲むばかりのような奴の。

Yon shadowy bark hath been to that wreck,

And the dim blue fire, that lights her deck,

Doth play on as pale and livid a crew

As ever yet drank the churchyard dew.

亡者の島へ、台風の目にあり、

亡者の島へ、恐るべき速さに、

帆という帆は巻き上げ骸骨かたどる、

舵取る手は此の世のものならず!

To Deadman’s Isle, in the eye of the blast,

To Deadman’s Isle, she speeds her fast;

By skeleton shapes her sails are furled,

And the hand that steers is not of this world!

急ぐべし、あなや!急げや急げ、

畏れ多き小帆船よ、夜が明ける前、

荒れ狂う天候しか朝に見せないように、

いつまでも青褪めているように、その赤い目の光に!

Oh! hurry thee on,—oh! hurry thee on,

Thou terrible bark, ere the night be gone,

Nor let morning look on so foul a sight

As would blanch forever her rosy light!

ヴァンダーデッケン望郷の便り、あるいは愛着ゆえの執着(1821)Vanderdecken's Message Home;*11 Or, The Tenacity Of Natural Affection

from BLACKWOOD'S EDINBURGH MAGAZINE No. L. MAY, 1821. Vol. IX.

from BLACKWOOD'S EDINBURGH MAGAZINE No. L. MAY, 1821. Vol. IX.

喜望峰に立ち寄って直ぐ、船はまた出て行った。やがて平卓山 the Table Mountain が見えなくなると、荒々しく襲い来る海、知られる限り他の大洋などよりずっと手強いと有名な海に揉まれ始めた。日は翳り霞んでいき、風も最前まで爽やかに吹いていたのが、時折ぱったり止んだと思うと短く強く吹き返し、風向きを変え、一時的に猛烈に吹き付けてはまた止みと、物悲しい綺想曲でも練習しているかのようだった。南東からは重々しいうねりが届き始めた。帆は帆柱に揺れ、船は右を左に転げ回ること、水浸しになりかねないばかり。舵を取ろうにもろくに風はなし。

Our ship, after touching at the Cape*12, went out again, and, soon losing sight of the Table Mountain, began to be assailed by the impetuous attacks of the sea, which is well known to be more formidable there than in most parts of the known ocean. The day had grown dull and hazy, and the breeze, which had formerly blown fresh, now sometimes subsided almost entirely, and then, recovering its strength for a short time, and changing its direction, blew with temporary violence, and died away again, as if exercising a melancholy caprice*13. A heavy swell began to come from the southeast. Our sails*14 flapped against the masts, and the ship rolled from side to side as heavily as if she had been water-logged. There was so little wind that she would not steer.

午後2時、雷雨を伴う突風を喰らう。船員たちは落ち着かず、前方不安に見守るばかり。この分では夜も酷かろう、ハンモックに潜り込む暇もないかもと皆が言う。二等航海士が、ニューファンドランドのレース岬で遭った強風を説明していた丁度その時、我々全員突然やられた、正にその猛烈な風圧が来た。

At 2 P.M. we had a squall, accompanied by thunder and rain. The seamen, growing restless, looked anxiously ahead. They said we would have a dirty night of it, and that it would not be worth while to turn into their hammocks. As the second mate was describing a gale he had encountered off Cape Race, Newfoundland, we were suddenly taken all aback, and the blast came upon us furiously.

夕暮れまで、二葉の主帆と前檣のトップセイルにて順走を続けたもの。しかし波が高くなると、船を停めた方がまだマシだと船長は判断した。

甲板上の当直4人のうち1人は、前を見張るよう命じられた。天候が非常に曇っており、船首から2鏈(れん)も見透せなかったため。

We continued to scud under a double-reefed mainsail and foretopsail till dusk; but, as the sea ran high, the captain thought it safest to bring her to. The watch on deck consisted of four men, one of whom was appointed to keep a lookout ahead, for the weather was so hazy that we could not see two cables' length*15 from the bows.

この男は、名をトム・ウィリスといい、何か観察するかのようにしげしげと船首へ行った。他の者が呼び止め、何を見ているのか尋ねてみても、はっきりとは答えようとせず。仕方なく皆も船首へ行き、驚愕を顕(あらわ)にし。やっと我に返った1人が叫んだ、「ウィリアム、人を呼べ!」と。

This man, whose name was Tom Willis, went frequently to the bows as if to observe something; and when the others called to him, inquiring what he was looking at, he would give no definite answer. They therefore went also to the bows, and appeared startled, and at first said nothing. But presently one of them cried, "William, go call the watch."

ハンモックで眠っていた船員たちは、時ならぬこの召喚に不満を鳴らし、甲板上でどうなっているのか聞こうとした。トム・ウィリス答えて、「上がって来て、見てくれ。気になるのは甲板の上ではなく、先にある」と。

The seamen, having been asleep in their hammocks, murmured at this unseasonable summons, and called to know how it looked upon deck. To which Tom Willis replied, "Come up and see. What we are minding is not on deck, but ahead."

これを聞くや、上着を着るのもそこそこに皆駆け出し、船首へ来て声を潜めた。

On hearing this they ran up without putting on their jackets, and when they came to the bows there was a whispering.

1人は尋ねる、「船って何処だ?俺には見えんぞ。」別の者が答えて、「さっきの電(いなづま)にちらりとあそこに見えたは、帆の1枚も畳んでいない。船歴から知れる限り、あの帆布で入港など全然していない筈なんだが。」

One of them asked, "Where is she? I do not see her." To which another replied, "The last flash of lightning showed there was not a reef in one of her sails; but we, who know her history, know that all her canvas will never carry her into port."

この時までに、船員たちの話声で、乗客数名が甲板に上がってきた。しかしながら誰も何も見えなかった。なぜなら、船は濃い闇に、叩きつける波の音に取り巻かれ、船員は寄せられた質問を避けていたから。

By this time the talking of the seamen had brought some of the passengers on deck. They could see nothing, however, for the ship was surrounded by thick darkness and by the noise of the dashing waters, and the seamen evaded the questions that were put to them.

この時点で、船の牧師が甲板に来た。厳粛にして謙虚な態度の男ゆえ、船員たちは『寛大なるジョージ殿』と呼んで敬愛したもの。彼は耳を欹(そばだ)てた、『飛んでいくオランダ人』を見たことがあるか、そしてその船にまつわる話を知っているかと別の者に尋ねる男に。聞かれた者は答えて、「かの船がこの海に揺れているとは聞いた。港に着くことがない理由は?」と。

At this juncture the chaplain*16 came on deck. He was a man of grave and modest demeanor, and was much liked among the seamen, who called him Gentle George. He overheard one of the men asking another if he had ever seen the Flying Dutchman before, and if he knew the story about her. To which the other replied, "I have heard of her beating about in these seas. What is the reason she never reaches port?"

言い出しっぺが答えて、「人により諸説ある中、俺が知る話はこうだ。アムステルダムの港から、70年前に出航した船があった。船の主の名は、ヴァンダーデッケン。頑固者の船乗りで、悪魔に向かってすら我が道を押し通す男であった。それでも、部下の水夫たちが文句をつけるようなことも絶えてなかった。…何でまた、そんな連中が乗り合わせたか不思議でならないが。

The first speaker replied, "They give different reasons for it, but my story is this: She was an Amsterdam vessel,*17's name was Vanderdecken. He was a staunch seaman, and would have his own way in spite of the devil. For all that, never a sailor under him had reason to complain, though how it is on board with them now nobody knows.

さて、物語だ。乗組員みな喜望峰へ身を屈しつつ、日がなテーブル湾、俺たちが今朝見たところへの風待ちをしていた。しかし、吹き付ける向かい風は、ますます強くなるばかり。甲板をそぞろ歩くは、風に向かって散々毒づく船長ヴァンダーデッケン。

The story is this, that, in doubling the Cape, they were a long day trying to weather the Table Bay, which we saw this morning. However, the wind headed them, and went against then more and more, and Vanderdecken walked the deck, swearing at the wind.

日没直後、とある船から問いかけること。その夜、湾に入るつもりではなかったかと。

ヴァンダーデッケン答えたもの、『永劫の罰を喰らおうと入ってやるか、さもなくば此の辺で浮き沈みしているかだ、裁きの日までも!』

Just after sunset a vessel*18 spoke him, asking if he did not mean to go into the bay that night. Vanderdecken replied, 'May I be eternally d--d if I do, though I should beat about here till the day of judgment!'

確かなことは、彼が湾に入ったことはない。だから彼は未だにこの海に揺られている、いつまでもそうしていると信じられている。この船は常に悪天候を纏い、人に見られることはない。」

And, to be sure, Vanderdecken never did go into that bay; for it is believed that he continues to beat about in these seas still, and will do so long enough. This vessel is never seen but with foul weather along with her."

また別の者が、「アレに近づかないようにしなければ。聞いた話ではあれの船長は、他の船が見えてくると、自ら端艇を操り並走し、手紙の束を押し付けようとするのだが。奴の言う事なぞ聞いていた日には、ろくな事にならないそうだ。」

To which another replied, "We must keep clear of her. They say that her captain mans his jolly-boat when a vessel comes in sight, and tries hard to get alongside, to put letters on board, but no good comes to them who have communication with him."

トム・ウィリスは、「今のところは距離があるのだから、そんな災難からは引き続き離れていたいね」と。

Tom Willis said, "There is such a sea between us at present as should keep us safe from such visits."

他の者は、「ヴァンダーデッケンが部下を派遣したところで、信用ならん」と。

To which the other answered, "We cannot trust to that, if Vanderdecken sends out his men."

この会話は少々、乗客にも漏れていて、ちょっとした騒ぎにもなった。その間、船を叩く波音は、遠くの雷音と区別もつかない勢いだった。|羅針盤の入った羅針箱(ビナクル)*19の光は風に消され、船の頭がどちらを向くのか誰にもわからない有様。

Some of this conversation having been overheard by the passengers, there was a commotion among them. In the meantime the noise of the waves against the vessel could scarcely be distinguished from the sounds of the distant thunder. The wind had extinguished the light in the binnacle, where the compass was, and no one could tell which way the ship's head lay.

乗客はもう質問するのもびくびくもの、全員を震え上がらせた謎めく恐怖感を積み増したり、既に知っている以上のことを教わったりしないよう。

しばらくの間は皆、心の動揺を悪天候に帰していたのだけれど、その不安も彼らが認めなかった原因から生じたのは、たやすく見て取れた。

The passengers were afraid to ask questions, lest they should augment the secret sensation of fear which chilled every heart, or learn any more than they already knew. For while they attributed their agitation of mind to the state of the weather, it was sufficiently perceptible that their alarms also arose from a cause which they did not acknowledge.

羅針箱のランプが再点灯し、船がこれまでよりも嵐に近づいていると解って、乗客も覚悟を決めた。

The lamp at the binnacle being relighted, they perceived that the ship lay closer to the wind than she had hitherto done, and the spirits of the passengers were somewhat revived.

しかしやはり、激しい低気圧も雷も止まらず、そしてすぐに、鮮やかな電が見せたのは、この船の周りに荒れ狂う波、そして沖合に『飛んでいくオランダ人』が、帆布一杯に風を孕み、猛烈な勢いで駆け抜ける。ほんの一瞬だったが、その光景は乗客の心から、すっかり疑いを払ってしまった。一人は大声で叫んだ、「あの船か!トガンまで全部、帆を揚げてるぞ」と。

Nevertheless, neither the tempestuous state of the atmosphere nor the thunder had ceased, and soon a vivid flash of lightning showed the waves tumbling around us, and, in the distance, the Flying Dutchman scudding furiously before the wind under a press of canvas. The sight was but momentary, but it was sufficient to remove all doubt from the minds of the passengers. One of the men cried aloud, "There she goes, topgallants*20 and all."

牧師は祈祷書を持ってきた。他の人たちの心を落ち着かせ、励ましてやるようなものを、そこから引き出してやろうとして。かくて本の白いページに光が当たるよう、羅針箱の近くに陣取った彼は厳粛な口調で、海で苦しんでいる人々のための貢献を読み上げた。水夫たちは腕を組んで立ちはだかり、何の役にも立たないことをと思っているようだった。しかしこれは、しばらくの間、甲板に居る人々の気を紛らわすには十分だった。

The chaplain had brought up his prayer-book, in order that he might draw from thence something to fortify and tranquillise the minds of the rest. Therefore, taking his seat near the binnacle, so that the light shone upon the white leaves of the book, he, in a solemn tone, read out the service for those distressed at sea. The sailors stood round with folded arms, and looked as if they thought it would be of little use. But this served to occupy the attention of those on deck for a while.

そのうち、電光は鮮明を欠くようになり、船の周りをうねる大波以外は、遠くも近くも見えなくなった。水夫たちは、まだ最悪の事態には至っていないと思っていたようだが、発言と予想を漏らさないよう気をつけていた。

In the meantime the flashes of lightning, becoming less vivid, showed nothing else, far or near, but the billows weltering round the vessel. The sailors seemed to think that they had not yet seen the worst, but confined their remarks and prognostications to their own circle.

この時、それまで寝台に居た船長が甲板に上がって来て、まるで空気を読まない陽気さで、蔓延する恐怖の原因を尋ねた。彼が言うには、皆が既に最悪の天気を経験しているのに、その部下共が軽風ひとつで騒ぎを起こしたとは何事かと思ったと。『飛んでいくオランダ人』に話が及ぶと、船長はげらげら笑って、「こんな夜更けにトガンセイルを揚げる船など是非とも見てやりたいものだ、さぞかし一見の価値があることだろうよ」と。

At this time the captain, who had hitherto remained in his berth*21, came on deck, and, with a gay and unconcerned air, inquired what was the cause of the general dread. He said he thought they had already seen the worst of the weather, and wondered that his men had raised such a hubbub about a capful of wind. Mention being made of the Flying Dutchman, the captain laughed. He said he would like very much to see any vessel carrying topgallantsails in such a night, for it would be a sight worth looking at.

船長の上着のボタンに牧師は手をかけ、脇に引っ張って、まじめな話をするよう注意した。すったもんだの末、船長は「そんなことより、この船の状況を見てくれ」と言われたのが耳に入り。そこで人を上にやり、どこもしっかりしているか確認させたのは、前檣の帆場辺り、大きな音で帆柱を擦っていたもので。

The chaplain, taking him by one of the buttons of his coat, drew him aside, and appeared to enter into serious conversation with him. While they were talking together, the captain was heard to say, "Let us look to our own ship, and not mind such things;" and, accordingly, he sent a man aloft to see if all was right about the foretopsail-yard, which was chafing the mast with a loud noise.

上がったのはトム・ウィリス。降りてきての報告に、どこもかっちり張ってあると。望むらくは早く晴れること、そして皆が何より恐れていたものを、これ以上見ずに済むようにと。

It was Tom Willis who went up; and when he came down he said that all was tight*22, and that he hoped it would soon get clearer; and that they would see no more of what they were most afraid of.

船長と一等航海士は一緒になって騒がしく笑うのが聞こえる程で、対して牧師は、そのような場所も弁えない騒々しさは抑えるべしと注意した。

The captain and first mate were heard laughing loudly together, while the chaplain observed that it would be better to repress such unseasonable gaiety.

スコットランド出身、ダンカン・サンダーソンという名の二等航海士は、アバディーンの大学に通ったこともある男で、水夫共の言うことなどあまり真に受けない方が賢明であると考えたか、船長の味方についた。トム・ウィリスに冗談めかして言ったもの、次に前方を見張る時は、おばあちゃんの眼鏡でも借りておけと。

The second mate, a native of Scotland, whose name was Duncan Saunderson, having attended one of the university classes at Aberdeen*23, thought himself too wise to believe all that the sailors said, and took part with the captain. He jestingly told Tom Willis, to borrow his grandam's spectacles the next time he was sent to keep a lookout ahead.

むっとしたトムは立ち去り、呟いていたのは、奴は自分の目で見たものでも朝になるまで信じるまいと。ただ言われた通りに船首に陣取り、相変わらず注意深く監視していたようだった。

Tom walked sulkily away, muttering, that he would nevertheless trust to his own eyes till morning, and accordingly took his station at the bow, and appeared to watch as attentively as before.

多くの人が寝床に戻ったので、話し声は止んだ。船がどしどしと海を進んでいくと、マストにロープがはじける音と、前方の大波がはじける音しか聞こえなかった。

The sound of talking soon ceased, for many returned to their births, and we heard nothing but the clanking of the ropes upon the masts, and the bursting of the billows ahead, as the vessel successively took the seas.

暗闇にかなりの間隔を置いて後、再び電光現れ出した。

トム・ウィリス突然叫んだ、「出た、ヴァンダーデッケン!ヴァンダーデッケンが!見えたぞ、奴ら端艇(ボート)を降ろしやがった」と。

But after a considerable interval of darkness, gleams of lightning began to reappear. Tom Willis suddenly called out, "Vanderdecken, again! Vanderdecken, again! I see, them letting down a boat."

甲板にいた全員が船首に駆け寄った。次の電光は、荒れ狂う海の上を遠く広く照らし出し、彼方の『飛んでいくオランダ人』号だけでなく、4人の男を乗せてやってくる端艇(ボート)も見せてくれた。端艇は此方の舷(ふなべり)から2鏈ばかり。これを最初に見た男は船長に駆け寄り、迎え入れてよいかどうか尋ねた。船長は大いに動揺して歩き回るばかり、返事もできず。

All who were on deck ran to the bows. The next flash of lightning shone far and wide over the raging sea, and showed us not only the Flying Dutchman at a distance, but also a boat coming from her with four men. The boat was within two cables' length of our ship's side. The man who first saw her, ran to the captain, and asked whether they should hail her or not. The captain, walking about in great agitation, made no reply.

一等航海士は叫んだ「誰か行ってあの端艇を係留するんだ」と。

The first mate cried, "Who's going to heave a rope to that boat?"

誰も何もしようとはせず、互いに促し合うばかり。端艇(ボート)が鎖のすぐ近くに来たとき、トム・ウィリスが叫んだ「何がしたい?それとも、こんな天気でどんな悪魔が、ここにお前らを吹き飛ばしたのか?」と。

The men looked each other without offering to do anything. The boat had come very near the chains, when Tom Willis called out, "What do you want? or what devil has blown you here in such weather?"

船からの声が嵐を貫き英語で答えた「船長と話したい」と。

A piercing voice from the boat replied, in English, "We want to speak with your captain."

船長はこれを無視、ヴァンダーデッケンの端艇(ボート)は接近し横並び。男が一人、甲板に上がって来て、風雨に晒され疲れ果てた船員のように見えたその手に手紙少々を抱えて。

The captain took no notice of this, and, Vanderdecken's boat having come close alongside, one of the men came upon deck, and appeared like a fatigued and weather-beaten seaman holding some letters in his hand.

水夫たちは皆引っ込んだ。引き換え、牧師は毅然として男を見つめ、数歩進んで尋ねた、「この訪問の目的は何ですか?」と。

Our sailors all drew back. The chaplain,*24 however, looking steadfastly upon him, went forward a few steps, and asked, "What is the purpose of this visit?"

見知らぬ人は答えた、「私たちは悪天候のために長い間ここに留まっており、ヴァンダーデッケンはこれらの手紙をヨーロッパの友人に送りたいと望んでいます」と。

The stranger replied, "We have long been kept here by foul weather, and Vanderdecken wishes to send these letters to his friends in Europe."

此方の船長は今になって前に出て、何とか格好つけて言うには「ヴァンダーデッケンは彼の手紙を、私のではなく他の船に託してくれたまえ」と。

Our captain now came forward, and said, as firmly as he could, "I wish Vanderdecken would put his letters on board of any other vessel rather than mine."

見知らぬ人は答えて、「私たちは多くの船に試みたが、それらのほとんどは私たちの手紙を拒否しました」と。

The stranger replied, "We have tried many a ship, but most of them refuse our letters."

トム・ウィリスは呟いた、「我々も同じことをするのが最善だろう。お前らの紙には時々、沈没する程の重さがあると言われているからな」と。

Upon which Tom Willis muttered, "It will be best for us if we do the same, for they say there is sometimes a sinking weight in your paper."

見知らぬ人はこれに気を止めず、私たちがどこから来たのか尋ねた。ポーツマスからだと言われると、強い感情を込めて言う「アムステルダムからだったらよかったのに。ああ、故郷よ!また友達に会わないと」と。彼がこれらの言葉を発したとき、下の端艇に乗っていた男たちは手を握りしめて泣き、鋭い口調のオランダ語で、「ああ、また会えたなら!ここで長い間浮沈してきたが、私たちはまた友達に会わなければ。」と。

The stranger took no notice of this, but asked where we were from. On being told that we were from Portsmouth, he said, as if with strong feeling, "Would that you had rather been from Amsterdam! Oh, that we saw it again! We must see our friends again." When he uttered these words, the men who were in the boat below wrung their hands, and cried, in a piercing tone, in Dutch, "Oh, that we saw it again! We have been long here beating about; but we must see our friends again."

見知らぬ人に牧師は尋ねて「あなたはどれくらい海にいましたか?」と。

The chaplain asked the stranger, "How long have you been at sea?"

彼は答えた、「年は数えられなくなりました。年鑑が船外に吹き飛ばされたので。ほら、私たちの船がそこに見えましょうに、どれほど海に居るのかお疑いですか?ヴァンダーデッケンは家に手紙を書き、友達を慰めたいだけです。」

He replied, "We have lost our count, for our almanac was blown overboard. Our ship, you see, is there still; so why should you ask how long we have been at sea? For Vanderdecken only wishes to write home and comfort his friends."

牧師はこう答えた。「思うにあなたの手紙は、たとえ配達されたとしても、アムステルダムでは用を成さないでしょう。宛てられた人たちは、もはや見つからないでしょう。教会の裏庭に古くからある緑の芝生の下以外には。」

To which the chaplain replied, "Your letters, I fear, would be of no use in Amsterdam, even if they were delivered; for the persons to whom they are addressed are probably no longer to be found there, except under very ancient green turf in the churchyard*25."

歓迎されない見知らぬ人は思わず両手を握り締め、泣いているように見えた。「有り得ない。信じられません。私たちは長い間ここを駆けてきたけれど、郷(くに)も親戚も忘れることはできません。雨粒は一滴も空中になくても、親類のように他の誰にも感じられ、海に降ってくれば再び一緒になります。親類たる者の血はその時、何処から来たのか、どうして忘れさせることが出来ましょう?まして私たちの身体と来ては、オランダの地の一部です。ヴァンダーデッケン申しますには、他所でくたばるくらいなら、アムステルダムに着くなり石の柱に変えられた方がまだマシだ、地面に嵌められ動けなくてもと。しかし、それはそれとして、私たちはあなたにこれらの手紙を受け取るようにお願いします。」

The unwelcome stranger then wrung his hands and appeared to weep, and replied, "It is impossible; we cannot believe you. We have been long driving about here, but country nor relations cannot be so easily forgotten. There is not a raindrop in the air but feels itself kindred to all the rest, and they fall back into the sea to meet with each other again*26. How then can kindred blood be made to forget where it came from? Even our bodies are part of the ground of Holland; and Vanderdecken says, if he once were to come to Amsterdam, he would rather be changed into a stone post, well fixed into the ground, than leave it again if that were to die elsewhere. But in the meantime we only ask you to take these letters."

牧師は驚きを以て彼を見つめ、「これは自然の愛情の狂気であり、時間と距離すべての尺度に反する」と述べた。

The chaplain, looking at him with astonishment, said, "This is the insanity of natural affection, which rebels against all measures of time and distance."

見知らぬ人は続けて、「二等航海士から、スタンケンのヨット埠頭2番の家に住む商人にして、彼の親愛なる唯一の友人である叔父への手紙です。」

The stranger continued, "Here is a letter from our second mate to his dear and only remaining friend, his uncle, the merchant who lives in the second house on Stuncken Yacht Quay."

彼はその手紙を差し出したが、誰もそれを受け取ろうとはしなかった。

He held forth the letter, but no one would approach to take it.

トム・ウィリスは声高に言った、「ここに居る者の一人は、去年の夏にアムステルダムに居たってんだが。スタンケンのヨット埠頭と呼ばれた通りなら、60年前に潰されてるって。今じゃそこにあるのは、でっかい教会1つきり。」

Tom Willis raised his voice and said, "One of our men, here, says that he was in Amsterdam last summer, and he knows for certain that the street called Stuncken Yacht Quay was pulled down sixty years ago, and now there is only a large church at that place."

『飛んでいくオランダ人』から来た男は、「有り得ない。信じられません。此方は別に、私からの手紙です。 私の愛する妹に銀行券を送って、洒落たレースを買って、高級な頭飾りにしてやろうという。」

The man from the Flying Dutchman said, "It is impossible; we cannot believe you. Here is another letter from myself, in which I have sent a bank-note to my dear sister, to buy some gallant lace to make her a high head-dress."

これを聞いたトム・ウィリスは、「その子の頭はもう墓石の下に違いない、ファッションの移り変わりよりずっと永いこと。それより、あんたの銀行券って、どの家の?」

Tom Willis, hearing this, said, "It is most likely that her head now lies under a tombstone, which will outlast all the changes of the fashion. But on what house is your bank-note?"

見知らぬ人は、「ヴァンダーブリュッカー社の銀行の」と答えた。

The stranger replied, "On the house of Vanderbrucker & Company."

トム・ウィリスに促された男は語った、「額面に及ばないかな、その銀行家は40年前に破産し、その後ヴァンダーブリュッカーは行方不明になったから。…しかし覚えておいてくれ、古い運河の底をかき集めるようなものだとは。」と。

The man of whom Tom Willis had spoken said, "I guess there will now be some discount upon it, for that banking house was gone to destruction forty years ago; and Vanderbrucker was afterward a-missing. But to remember these things is like raking up the bottom of an old canal."

見知らぬ人は、「有り得ない。信じられません!こんな状態の我々に、そんなことを言うとは残酷な。

…私たちの船長からは、彼の愛する貞節な妻への手紙があります。ハーレマー・マーの国境にある快適な夏の別荘に置いてきた彼女は、彼が戻ってくる前に家を美しく塗装して金メッキし、主室用の新しい姿見を手に入れることを約束しました。ヴァンダーデッケンが映れば、一度に6人の夫がいるかのような。」

The stranger called out, passionately, "It is impossible; we cannot believe it! It is cruel to say such things to people in our condition. There is a letter from our captain himself, to his much-beloved and faithful wife, whom he left at a pleasant summer dwelling on the border of the Haarlemer Mer. She promised to have the house beautifully painted and gilded before he came back, and to get a new set of looking-glasses for the principal chamber, that she might see as many images of Vanderdecken as if she had six husbands at once."

男は答えた、「それ以来、夫が6人替わる程の時間が経った。彼女がまだ生きていても、ヴァンダーデッケンが家に帰って邪魔をする恐れはあるまいよ」と。

The man replied, "There has been time enough for her to have had six husbands since then; but were she alive still, there is no fear that Vanderdecken would ever get home to disturb her."

これを聞くや、見知らぬ人は再びはらはら涙を流し、手紙が受け取られない以上、立ち去るしかありますまいと言う。そして周りを見回し、船長、牧師、そして残りの乗組員に小包を次々と差し出したところが、めいめいが手を後ろにやり、差し出された分だけ退き下がる。仕方なくその手紙を甲板に置き、吹き飛ばされないよう、近くに落ちていた鉄片を重しに置いた。こうして後、よろよろと舷門を抜け、端艇(ボート)に乗り込んだ。

On hearing this the stranger again shed tears, and said if they would not take the letters he would leave them; and, looking around, he offered the parcel to the captain, chaplain, and to the rest of the crew successively, but each drew back as it was offered, and put his hands behind his back. He then laid the letters upon the deck, and placed upon them a piece of iron which was lying near, to prevent them from being blown away. Having done this, he swung himself over the gangway, and went into the boat.

他の人が話しかけるのが聞こえたが、俄に突風巻き起こり、彼の返事は聞き取れず。端艇(ボート)が舷を離れるのが見え、しばらくするともう、その痕跡はほとんどなく、何もそこになかったようだった。船員たちは自分が見たものを信じられずに目を擦ったが、小包は甲板に置かれたままで、全て現実であったことの証を立てていた。

We heard the others speak to him, but the rise of a sudden squall prevented us from distinguishing his reply. The boat was seen to quit the ship's side, and in a few moments there were no more traces of her than if she had never been there. The sailors rubbed their eyes as if doubting what they had witnessed; but the parcel still lay upon deck, and proved the reality of all that had passed.

スコットランド人の航海士ダンカン・サンダーソンは船長に、手紙を取り上げて郵便鞄に入れるべきかどうか尋ねた。返事がなかったので、誰もあんなものに触れてはダメだと窘めつつトム・ウィリスが引き戻していなかったら、ダンカンは手紙を持ち上げていた事だろう。

Duncan Saunderson, the Scotch mate, asked the captain if he should take them up and put them in the letter-bag. Receiving no reply, he would have lifted them if it had not been for Tom Willis, who pulled him back, saying that nobody should touch them.

そのうち船長は船室に降り、牧師は彼を追いかけ、酒棚のところで見つけ、ブランデー一杯を注いでやった。船長はやや戸惑ったものの、すぐにグラスを差し出し、「お墨付きとは、この夜寒に有難いものだ」と言った。

In the meantime the captain went down to the cabin, and the chaplain, having followed him, found him at his bottle-case pouring out a large dram*27 of brandy. The captain, although somewhat disconcerted, immediately offered the glass to him, saying, "Here, Charters*28, is what is good in a cold night."

牧師は一切飲みはせず、船長は成果を飲み込み、二人とも甲板に戻ると、船員が手紙をどうするべきか意見を交わしているところだった。トム・ウィリスは、銛で串刺し、船外に放り出そうと提案した。

The chaplain declined drinking anything, and, the captain having swallowed the bumper, they both returned to the deck, where they found the seamen giving their opinions concerning what should be done with the letters. Tom Willis proposed to pick them up on a harpoon, and throw it overboard.

別の者が言うには、「俺がよく聞かされた話では、いずれにせよ安全ではない。受け入れようと、投げ出そうと」と。

Another speaker said, "I have always heard it asserted that it is neither safe to accept them voluntarily, nor, when they are left, to throw them out of the ship."

「誰も触らないように」と整備工は言った。「『飛んでいくオランダ人』からの手紙の始末は、奴等がもし回収しようとしたら渡せるよう、箱詰めして甲板に釘付けておくことです。」

"Let no one touch them," said the carpenter. "The way to do with the letters from the Flying Dutchman is to case them up on deck, so that, if he sends back for them, they are still there to give him."

整備工は自分の道具を取りに行った。行ってしまった間に、船は強烈な縦揺れを起こし、それで手紙から鉄片が滑り落ち。風に飛ばされ船外に渦巻いたこと、凶兆の鳥が空中に渦巻くよう。水夫たちに喜びの大歓呼。そしてすぐに起こった天候の好ましい変化を、皆ヴァンダーデッケンの消滅に帰した。こうして漸く、航路に復する。夜間当直が置かれ、残りの乗組員は寝床に退った。

The carpenter went to fetch his tools. During his absence the ship gave so violent a pitch that the piece of iron slid off the letters, and they were whirled overboard by the wind, like birds of evil omen whirring through the air. There was a cry of joy among the sailors, and they ascribed the favourable change which soon took place in the weather to our having got quit of Vanderdecken. We soon got under way again. The night watch being set, the rest of the crew retired to their berths.

終。

結局、ヴァンダーデッケン船長その人は描かれていない。そちらはフレデリック・マリアット『幽霊船』(1839)の印象があったのだろう。

この話は『さまよえるオランダ人』の要素を多く含むも、救済については一切、言及がない。ワーグナー台本の中心をなす女性の犠牲はマルシュナーのオペラ『吸血鬼』及びポリドリの原作から、その愛と献身による救済はハイネの小説から持ってきたものらしい。

*1:アールネ・トンプソンのタイプ・インデックス(英: Aarne-Thompson type index、AT分類)とは、世界各地に伝わる昔話をその類型ごとに収集・分類したもの。

*2:cape は一般的に岬を言うが、the Cape というときは喜望峰を指す。

*3:ナポレオンの流刑地になったセントヘレナ島は、大西洋の南半球側、ややアフリカ寄りにある。喜望峰からは距離があるけれど、荒れ模様の空には何処でも幽霊船が出現すると信じられたようだ。

*4:単縦陣を組む戦列艦をいう。英語では船舶一般を女性名詞とするのに対し、「男の船」を強調し "man of war ship" と呼んだものが、後に ship を外した。しかしそれなら、『さまよえるオランダ人』は商船ではなく戦闘専門の、かなり強力な軍艦で、オペラの想定とは異なるのではないか。重い艦砲を舷側に多数配備し、砲弾を備蓄した軍艦には、商品を積み込む余裕はない

*5:船首の風下となる側。適切な訳語見当たらず

*6:gunports

*7:port としか言っていないが、小窓を開けた程度で怯える理由にはならない。『さまよえるオランダ人』号は全砲門を開き、艦砲の発射準備を整え、敵対行動というか掠奪の構えを見せたから、海賊の害を恐れた訳である

*8:アシュリマン教授の引用文では pot に作るが、おそらく原典の汚損

*9:アシュリマン教授の引用文では founder に作るが、訳すと意味が通らない。これに限らず、f と記した文字が s の綴り違いと思われる箇所があり、原典を見ると、long s と呼ばれる f によく似た ſ の写し損ねであろう。古英語のアルファベットは、現在のものと異なるところがあり、写本によっても異なる事があり、どうやら発音話し方も異なっていたので、著作権のない古典も案外と面倒臭い。

*10:「台風の目」の事と思われるが、Typhoon とは書いていない

*11:オランダ人船長のこの名は、出版物ではこれが初出と見られている。しかしこの話の中では、以前から有名だったように書かれている。Wikipedia でフルネームを Hendrik Van Der Decken とするのは典拠不明。そもそも deck は『天井』『甲板』を指すドイツ語、decken はその動詞であるから、オランダ人船長に相応しい人名とも思えない。もっとも、アンドレ・ヴァンデルノート(André Vandernoot, 1927 - 1991)というベルギーの指揮者も居たから、似たような名の者は在ったかもしれない。この読み方に倣うと、「ヴァンデルデッケン」が現地読みに近いと思われる。英語読みだと「ヴァンダーデッケン」になる。

*12:cape は「岬」。中でも the Cape というと、ほぼ喜望峰 Good Hope Cape 及びケープタウンを意味する。

*13:パガニーニ24のカプリッチョは、1820年出版。凄まじい評判を得たその翌年に本作の発表であるから、作者も読者もこれを意識したであろう。後にリストやシューマンも、ピアノ独奏用に編曲している。

*14:帆船の帆は幾つにも分かれ、呼び名も統一されず、適切な訳語が判らない。とりあえず Wikipedia に拠る

*15:鏈(れん)。海上距離の単位、通例100尋すなわち1/10海里 = 185m

*16:病院・刑務所・軍隊・学校などの組織に所属する牧師。特に軍隊付の牧師は「従軍牧師」と訳されるが、chaplain は必ずしも従軍する牧師ではない。

*17:)) and sailed from that port seventy years ago. Her master((持ち主の意味の『船主』ではなく、『船長』であろう。以下は『船長』とする。

*18:She とはされていないので、別の船からの呼びかけ。当時は、船団を組んでの航海が普通だった。

*19:羅針盤その他の航法装置を格納し、操舵手の眼前に見易く保持する構造物。計器の照明を内蔵する。

*20:上檣[帆]。大型の帆船では横帆を分割して張る。下からコースセイル、トップセイル、トップセイルの上がトガンセイル。セイルは「スル」と省略して呼ばれることがある。top and top-gallant または top and topgallant という言い方で「帆を全部揚げて」「全速力で」の意味になる。

*21:船の寝床。船長が寝床に居たというのは、つまり一杯やっていた訳である。

*22:酔っ払った船長が all was right か見てこいと命じたので、このように洒落で返した。

*23:スコットランド北東の港町アバディーンの大学は、イギリスでも五指に入る古来の名門。そんなところに通った航海士というのは、エリート船員と目される。

*24:頼りにならない The captain に代わって、The chaplain が根性を見せ、結果として見せ場を作る。本作が緊迫した場面の合間にこうした駄洒落を挟むのは、航海の実際に近いのではないか。

*25:西洋における教会の裏庭は、墓地になっている。

*26:何かの引用句に見えるが、出典不明。

*27:少量の洋酒。語源はラテン語の重量単位"drachm"

*28:人名・地名でもあるが、『憲章』でもあり、単数形では『公認』を意味する。牧師から酒を勧められ、おどけて言ったもの。

クビライ・カーン上都におはして

クビライ・カーン上都におはして

真夜中打ったはお城の時計、

真夜中打ったはお城の時計、

素早く立って、素早く揃えた

素早く立って、素早く揃えた![マルシュナー:歌劇「吸血鬼」(Der Vampyr)[2CDs] マルシュナー:歌劇「吸血鬼」(Der Vampyr)[2CDs]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41tvJY8vnOL._SL500_.jpg)